Virginia Giuffre’s posthumous memoir begins with a 15-year-old girl sitting by a road in Florida. Her face is swollen, her throat is bruised and she’s “bleeding from places she didn’t know she could bleed”. She has just been raped at gunpoint in a motel room by a man who gave her a lift after she fled the juvenile detention centre in Palm Beach.

“Stay here,” her attacker told her as he left the room. “Try to leave and I’ll find you and kill you.” Within a couple of years, she’ll meet Jeffrey Epstein, Prince Andrew and many more men. The rest, unfortunately, we know – but you may not know it in as much detail as you’re about to get.

There are times while reading Nobody’s Girl, which is being published six months after Giuffre, 41, took her own life, when you think: how much can one person endure? Her father, she alleges, starts abusing her when she’s still in single digits. He lets his neighbour rape her first. “Sometimes what they each did to me was so similar that I suspected they were comparing notes,” she writes. (Today, he “strenuously denies” all her allegations, a denial that co-writer Amy Wallace diligently records in her introduction.)

Later, while living in a children’s home where she endures further physical and psychological abuse, Giuffre is raped by two boys in the back of a car. And, soon after the motel room rape described above, she’s picked up by Ronald Eppinger, a Miami-based man who tells her he runs a modelling agency. In truth, he’s a sex trafficker. At this point, she’s still barely 15.

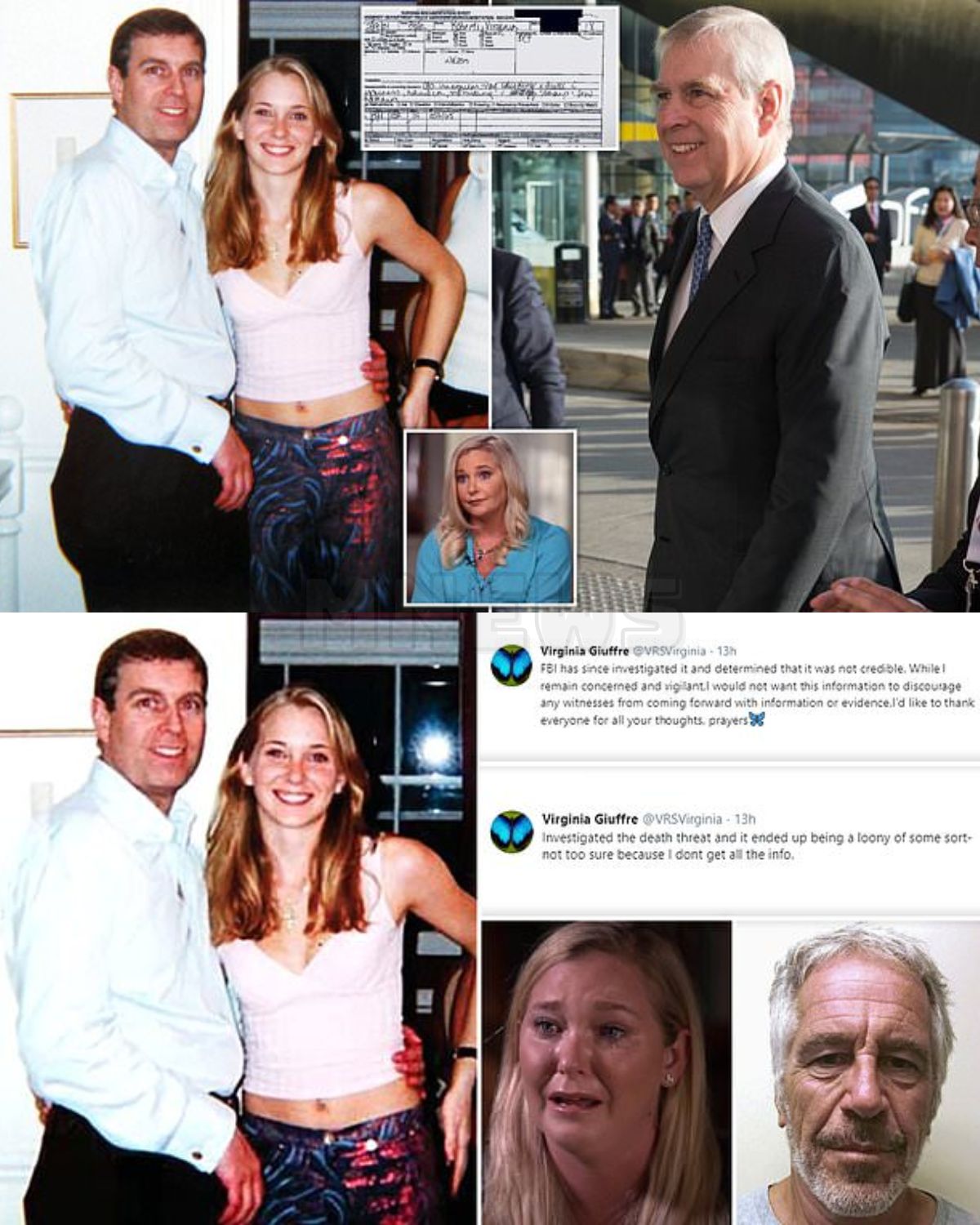

The most sensational lines from Giuffre’s memoir concern the next few years, and these have, in the last week, been extensively leaked. The Royal family may, if anything, be oddly relieved that Nobody’s Girl contains few new allegations about Prince Andrew, but the ones Giuffre repeats here – having described them in court years ago – lose nothing of their horror.

Giuffre alleges that the former Duke of York – stripped in recent days of that title – had sex with her three times. “He was particularly attentive to my feet,” she writes of their first encounter, “caressing my toes and licking my arches.” (Prince Andrew continues to deny the allegations, as he always has.)

No single headline can convey the whole sorry, sordid mess of Giuffre’s story, which is steadfastly recounted here with the help of Wallace, an experienced journalist, in clear-eyed (if not always cliché-free) prose. Young Virginia never has anywhere to go. Her mother is portrayed as emotionally distant and even neglectful. The neighbour who raped her with the blessing of Virginia’s father has a religious conversion, and tells her what happened was her fault.

After she flees Eppinger, she finds work as a locker-room assistant at Donald Trump’s resort, Mar-a-Lago. There, she meets Ghislaine Maxwell, who sounds like “Mary Poppins”, and invites her to come and work as a masseur for Epstein, who at his and Giuffre’s first meeting is lying naked on a bed. Maxwell orders 16-year-old Giuffre to take off her clothes. “How cute – she still wears little girl’s panties,” Epstein says. Then he abuses her.

Before long, Giuffre is working as an effective sex-slave for Epstein; he has given her a wad of cash that enables her to move into her own apartment. Some of the most minor casual details from this period – in which she is hired out to pleasure businessmen and billionaires – are among the most revolting. Epstein paints the walls of his house pink – “I love pink. Pink is for pussy!” – and keeps penis- and vagina-shaped soaps in the bathrooms. Another time, she’s so badly beaten by a man she names only as “the Minister” that she can’t walk without pain for three days.

Epstein’s own tastes turn dark. Giuffre is sometimes “gagged and hog-tied”. Yet she doesn’t attempt to leave. A complex relationship emerges – a perverted facsimile of family life. There are popcorn evenings in front of the TV and walks along the beach with Maxwell, collecting driftwood. “Epstein sometimes insisted I call him ‘daddy’ during sex,” she writes. And: “I was no expert on mothers but in those early days, I sometimes imagined Maxwell as mine.” She is so desperate to make Epstein proud that she starts hanging around schools in New York at 3pm, to recruit young girls she thinks he will like.

Nobody’s Girl feels like an act of defiance not just against those who terrorised her for so long – Epstein once demanded Giuffre’s silence by showing her a photograph of her beloved younger brother – but also those who, over the years, queried her version of events. I don’t wish to join their ranks – who would? – but, as a critic, I feel bound to say that some of the testimony here feels unsatisfyingly neat.

She explains the existence of the famous photograph with Prince Andrew (above), for instance, which she apparently insisted be taken, by saying “I knew my mum would never forgive me if I met someone as famous as Prince Andrew and didn’t pose for a picture” – which, given the circumstances, feels almost too odd to believe. Memory can do strange things.

Moreover, the story is deeper and darker than this book can say: any intelligent reader knows that there are many famous names connected to Epstein who do not appear in Giuffre’s pages. (Nor, for what I suspect may be similar reasons, can they appear on this one.)

But these are cold criticisms. On the whole, Virginia Giuffre doesn’t deserve our scrutiny so much as our admiration. And in helping to bring Epstein and Maxwell to justice at a titanic personal cost, she deserves our, and many other women’s, thanks.